A more detailed version of this post can be found on the Finnish Institute blog.

The Finnish Institute in London has recently completed a five-month research

project on the British open data policies. The report looks at how the open data

ecosystem has emerged in the UK and what lessons can be drawn from the

British experiences. The year 2012 will be a big year for open data in Finland,

and this report also partly aims at further facilitating the development of open

knowledge in Finland.

In short, the key arguments that the research makes can be listed as follows:

- The key to securing the benefits of open data is the quality of user engagement

- Open data and its objectives should be addressed as a part of the freedom-of-information continuum

- The decision to emphasise the release of expenditure data was not ideal: governments do not know best what kind of data people want to have and should aim at releasing it all

- Leadership, trust and IT knowledge are crucial, not only for political leadership but within organisations too

- The social and democratic impacts of open data are still unclear and in future there is a need for sector-specific research

After a series of interviews and analysis of government documents it became evident that open data is not as apolitical an initiative as many may assume it to be. There is a long history of politicised debate on transparency and public spending behind the initiative.

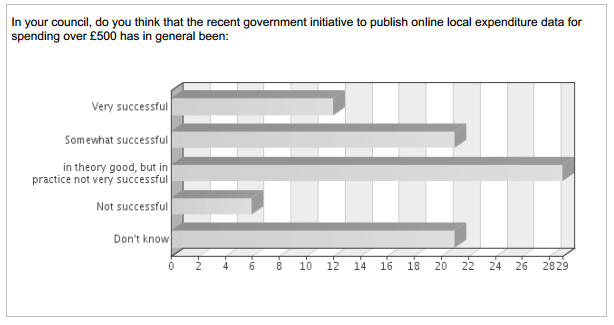

It seems that public sector data providers are supportive towards the idea of data transparency itself, but very cautious towards the means of achieving it, especially the initiative of releasing the data of expenditure over £500 in local government. At the same time, the open data community should not overestimate the general level of interest towards data.

Open data is applied in various ways with lots of small-scale success stories available, mostly in the form of mobile-phone or web applications. These services make everyday life of citizens a tiny bit easier, and when accumulated they may result in significant economic benefits. However, the open-data community has also been vocal about the potential positive impacts on democracy. These impacts are significantly harder to identify and need much more research in order to produce comprehensive and reliable results.

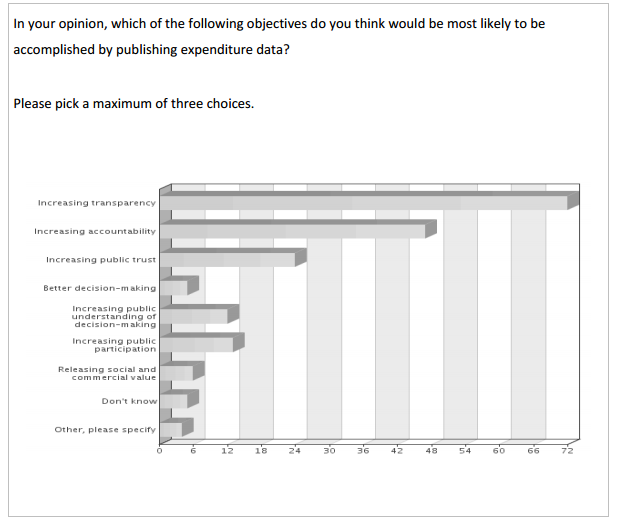

The report argues that the applicability of data is effectively linked to the initial objectives of open data. The value of open data is built on an uncertain variable and on how people use it – it is difficult to form a single “one size fits all” model, to measure the value of applicability. In addition, we must realise the difference between transparency and democracy-oriented goals that are usually associated with the freedom-of-information movement and the technology and innovation-oriented goals of the open-data movement. The overall value of transparency is, however, not something that should be measured primarily in financial profits.

Economic impacts can be measured relatively easily with the current methods, but the possible changes in our society due to digitisation of the core infrastructures and the abilities of citizens to manage their lives within it pose challenges for the legitimate and democratic transparency regime. In the future, it is more important to focus on the normative side of open data and on its potential impacts on democracy. There is a risk of creating a hollow mantra of open data improving the level of democracy without any evidence provided. However, the potential for great improvement in democratic accountability is there.

Truly democratic transparency requires more than just the release of open data. It needs citizens who can see that their interests are treated equally in society. If it is hoped that open data will provide the catalyst for this, then the thresholds for access, use and interpretation of data need to be as low as possible. In order to achieve this, the data producers must possess a certain level of ICT knowledge to implement the system so that it is both simple enough to use and sophisticated enough to be able to manage information flow comprehensively – knowledge which is often lacking. This should not be an excuse not to release data, however, but a wake-up call for both data providers and the open-data community alike.

The Finnish Institute continues its work with open knowledge in all its forms and is happy to be a partner organisation in the upcoming Open Knowledge Festival in Helsinki. The final report “Being Open About Data – analysis of the UK open data policies and applicability of data” can be read and downloaded here.

Antti is doing a PhD at the University of Helsinki, and is a Fellow at the Finnish Institute of London. The Finnish Institute is a London-based private trust, whose mission is to identify emerging issues relevant to contemporary society and to act as catalyst for positive social change through partnerships. The Reports of the Finnish Institute in London is a series of publications, which publishes research, studies and results of collaborative projects carried out by the institute. The reports provide evidence and ideas for policymakers and civic society organisations dealing with contemporary social and cultural challenges.

1 thought on “Being Open About Data”

Comments are closed.