This is a guest post, originally published in French on the Open Knowledge Foundation France blog

Nowadays, being able to place an address on a map is an essential information. In France, where addresses were still unavailable for reuse, the OpenStreetMap community decided to create its own National Address Database available as open data. The project rapidly gained attention from the government. This led to the signing last week of an unprecedented Public-Commons partnership between the National Institute of Geographic and Forestry Information (IGN), Group La Poste, the new Chief Data Officer and the OpenStreetMap France community.

In August, before the partnership was signed, we met with Christian Quest, coordinator of the project for OpenStreetMap France. He explained the project and its implications to us.

Here is a summary of the interview, previously published in French on the Open Knowledge Foundation France blog.

Why Did OpenStreetMap (OSM) France decided to create an Open National Address Database?

The idea to create an Open National Address Database came about one year ago after discussions with the Association for Geographic Information in France (AFIGEO). An Address Register was the topic of many reports however these reports can and went without any follow-up and there were more and more people asking for address data on OSM.

Address data are indeed extremely useful. They can be used for itinerary calculations or more generally to localise any point with an address on a map. They are also essentials for emergency rescues – ambulances, fire-fighters and police forces are very interested in the initiative.

These data are also helpful for the OSM project itself as they enrich the map and are used to improved the quality of the data. The creation of such a register, with so many entries, required a collaborative effort both to scale up and to be maintained. As such, the OSM-France community naturally took it over. However, there was also a technical opportunity; OSM-France had previously developed a tool to collect information from the french cadastre website, which enabled them to start the register with significant amount of information.

Was there no National Address Registry project in France already?

It existed on papers and in slides but nobody ever saw the beginning of it. It is, nevertheless, a relatively old project, launched in 2002 following the publication of a report on addresses from the CNIG. This report is quite interesting and most of its points are still valid today, but not much has been done since then.

IGN and La Poste were tasked to create this National Address Register but their commercial interests (selling data) has so far blocked this 12-year old project. As a result, a French address datasets did exist but these datasets were created for specific purposes as opposed to the idea of creating a reference dataset for French addresses. For instance, La Poste uses three different addresses databases: for mail, for parcels, and for advertisements.

Technically, how do you collect the data? Do you reuse existing datasets?

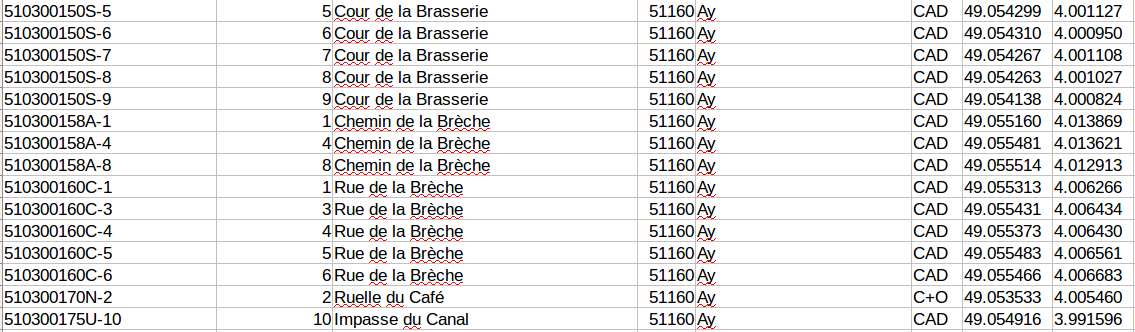

We currently use three main data sources: OSM which gathers a bit more than two million addresses, the address datasets already available as open data (see list here) and, when necessary, the address data collected from the website of the cadastre. We also use FANTOIR data from the DGFIP which contains a list of all streets names and lieux-dits known from the Tax Office. This dataset is also available as open data.

These different sources are gathered in a common database. Then, we process the data to complete entries and remove duplications, and finally we package the whole thing for export. The aim is to provide harmonised content that brings together information from various sources, without redundancy. The process is run automatically every night with the exception of manual corrections that are done from OSM contributors. Data are then made available as csv files, shapefiles and in RDF format for semantic reuse. A csv version is published on github to enable everyone to follow the updates. We also produce an overlay map which allows contributors to improve the data more easily. OSM is used in priority because it is the only source from which we can collaboratively edit the data. If we need to add missing addresses, or correct them, we use OSM tools.

Is your aim to build the reference address dataset for the country?

This is a tricky question. What is a reference dataset? When you have more and more public services using OSM data, does that mean you are in front of a reference dataset?

According to the definition of the French National Mapping Council (CNIG), a geographic reference must enable every reuser to georeference its own data. This definition does not consider any particular reuse. On the other hand, its aim is to enable as much information as possible to be linked to the geographic reference. For the National Address Database to become a reference dataset, it is imperative that data is more exhaustive. Currently, there is data for 15 million reusable addresses (August 2014) of an estimated total of about 20 million. We have more in our cumulative database, but our export scripts ensure there is a minimum quality and coherency and release only after the necessary checks have been made. We are also working on the lieux-dits which are not address data point, but which are still used in many rural areas in France.

Beyond the question of the reference dataset, you can also see the work of OSM as complementary to the one of public entities. IGN has a goal of homogeneity in the exhaustivity of its information. This is due to its mission of ensuring an equal treatment of territories. We do not have such a constraint. For OSM, the density of data on a territory depends largely on the density of contributors. This is why we can offer a level of details sometimes superior, in particular in the main cities, but this is also the reason why we are still missing data for some départements.

Finally, we think to be well prepared for the semantic web and we already publish our data in RDF format by using a W3C ontology closed to the European INSPIRE model for address description.

The reached agreement includes a dual license framework. You can reuse the data for free under an ODbL license, or you can opt for a non-share-alike license but you have to pay a fee. Is share-alike clause an obstacle for the private sector?

I don't think so because the ODbL license does not prevent commercial reuse. It only requires to mention the source and to share any improvement of the data under the same license. For geographical data aiming at describing our land, this share-alike clause is essential to ensure that the common dataset is up to date. Lands change constantly, data improvements and updates must, therefore, be continuous, and the more people are contributing, the more efficient this process is.

I see it as a win-win situation compared to the previous one where you had multiple address datasets, maintained in closed silos with none of which were of acceptable quality for a key register as it is difficult to stay up to date on your own.

However, for some companies, share-alike is incompatible with their business model, and a double licensing scheme is a very good solution. Instead of taking part in improving and updating the data, they pay a fee which will be used to improve and update the data.

And now, what is next for the National Address Database?

We now need to put in place tools to facilitate contribution and data reuse. Concerning the contribution, we want to set-up a one-stop-shop application/API, separated from OSM contribution tool, to enable everyone to report errors, add corrections or upload data. This kind of tool would enable us to easily integrate partners into the project. On the reuse side, we should develop an API for geocoding and address autocompletion because not everybody will necessarily want to manipulate millions of addresses!

As a last word, OSM is celebrating its ten years anniversary. What does that inspire you?

First, the success and the power of OpenStreetMap lies in its community, much more than in its data. Our challenge is therefore to maintain and develop this community. This is what enables us to do projects such as the National Addresses Database, but also to be more reactive than traditional actors when it is needed, for instance with the current Ebola situation. Centralised and systematic approaches for cartography reached their limits. If we want better and more up to date map data, we will need to adopt a more decentralised way of doing things, with more contributors on the ground. Here’s to Ten More Years of the OpenStreetMap community!