We’re in the planning stages of a conflict prevention project called PAX and open data perspectives have fed into our thinking in its processes and structures.

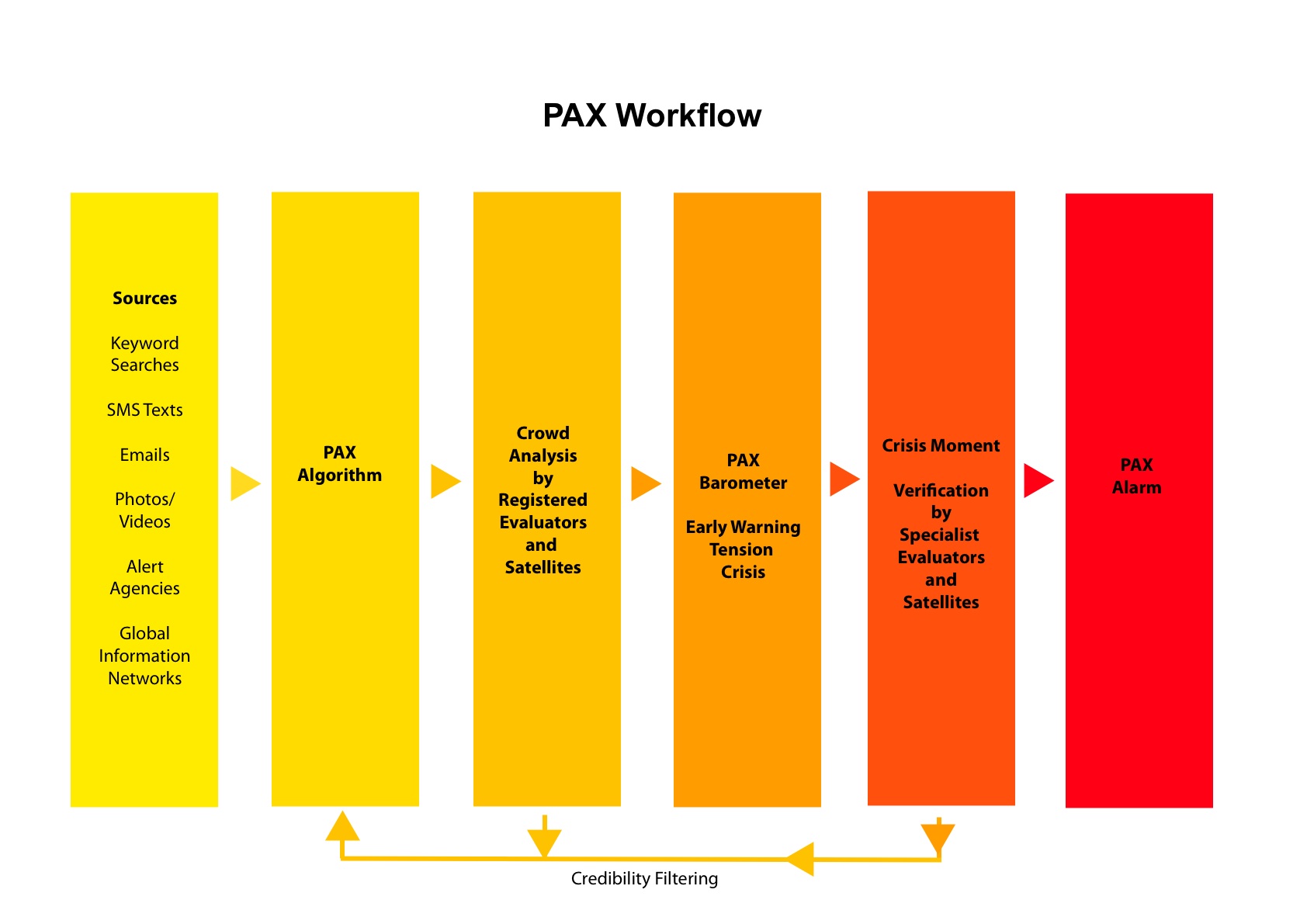

PAX aims to provide early warnings of emerging violent conflict, through an online collaborative system of data sharing and analysis. We’re still in the early stages of exploration and experiment, but the principle is that open data could help provide warnings of emerging violent conflict, enabling governments, NGOs and citizens to take action to prevent it escalating. PAX’s premise is that by collaborating on timely analysis of data, we may be able to ring the alarm on emerging situations much faster than with yesterday’s closed and hierarchical systems.

Openness permeates PAX’s approach, from data to processes to software. Our sources would include everything that we can get governments, NGOs and corporations to share, in addition to the direct voice of conflict-affected people –

through citizen reporting, mobiles, social media and so on. We’re looking at using open source software for sharing and reporting, with Ushahidi’s original mapping platform and their soon-to-be released revamped SwiftRiver platform.

SwiftRiver is a platform for sorting through huge flows (rivers) of information in times of crisis. It uses crowdsourcing methods not only to gather information, but also in the process of sorting and analysis. Those with local knowledge and local language are invited to join a transparent conversation about the value of any one piece of data – Is it of questionable authenticity? Could it be false information put out by the perpetrators of violence? Is it out of date? What’s the location?

With the results of that analysis, citizens can hold their governments to account on their efforts to prevent conflict. We hope to provide a new lever with which to ask governments to fulfil their responsibility to protect where populations are in danger.

The #Kony2012 campaign from Invisible Children demonstrated the power of a population calling on their government to take action to prevent Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) atrocities. But the information they presented to

their public was widely criticised for being inaccurate and out of date. Wouldn’t this type of call to action be more powerful where the information on perpetrators of violence against civilians was more accurate and timely, through online verification, amplifying the voices of affected people?

Opening up direct communication with conflict-affected people could enable them to ask for the kind of action and resources they really want. Less well-known is the Invisible Children’s LRA Tracker project (a collaboration with

Resolve) which uses mapping and realtime reporting (including reports from people affected in the region) to shine a light on LRA attacks throughout the remote border area between Democratic Republic of Congo, South Sudan and

Central African Republic.

The pressure for openness, more information, transparency and the existence

of many non-governmental projects seeking to open up satellite imagery to the

wider public, is contributing to an environment where the governments are increasingly willing to share

their own government data on conflict regions. Following a stream of satellite imagery projects to document human rights abuses (see George Clooney’s Satellite Sentinel project, and Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch among others), a number of declassified images of Homs in Syria were publicly released by the US government (through US Ambassador Ford’s Facebook page), in a new move to expose atrocities there.

Some of the most interesting projects have got stuck in early on, so that they are prepared and proactive when it comes to gathering and analysing realtime data. The Syria Tracker crisismapping deployment launched shortly after the

protests began and is now the longest running mapping project covering the violence across the country. Working with volunteers both within and outside Syria, they are systematically recording information, mapping it, and creating a vital record of atrocities by the Syrian government.

Here we have civilians collecting and publishing data which governments are certainly not publishing, and may not even be collecting. This form of openness by citizens puts pressure on governments to improve their own documentation and publication – and we hope it may also encourage them to respond to events in the way that the people on the ground want them to.

We’d love to hear your thoughts and comments on the project, you can find out more at http://www.paxreports.org/.

Catherine Dempsey is a Research Consultant at PAX.

2 thoughts on “Can Open Data help conflict prevention?”

Comments are closed.