The following post is by Francis Irving, CEO of ScraperWiki.

Can you think of an open data curation project where the people who work on it come from multiple commercial companies?

In the mid 1990s, as open source code began to boom, the equivalent was commonplace. Geeks working at ISPs would together patch the Apache webserver into shape. Startups like RedHat would pay for staff to work on lots of projects in order to produce a whole operating system.

For years I’ve asked, where are the equivalent projects in open data?

Nada.

Not one.

Until today. I finally found one.

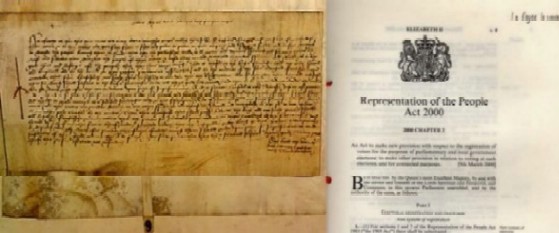

It’s the UK’s Statute Law database, which is maintained by the National Archives. I explained back in 2006 how it used to be proprietary data, and how it was finally opened up in an incomplete form.

Briefly, Parliament doesn’t release a usable set of laws. They release Acts, which are changes to laws (patch files, if you’re a geek). These need to be “consolidated” with existing laws into the actual rules we have to obey.

Two commercial companies (LexisNexis and Westlaw, so called after centuries of takeovers) do this consolidation themselves. They charge a handsome price. Nobody can compete with them, as they don’t have the current laws to start from, even if they had the money to keep up with new changes.

I spent a chunk of yesterday afternoon talking to John Sheridan (right) from the National Archives. He runs the Government’s Statute Law project. Jeni Tennison (left) is his technical mastermind. Last time I spoke to her a year or two ago she was worried that they would never finish the work. The sheer volume of new laws and difficulty of consolidations seemed insurmountable. Would they ever have a complete image of current law?

I spent a chunk of yesterday afternoon talking to John Sheridan (right) from the National Archives. He runs the Government’s Statute Law project. Jeni Tennison (left) is his technical mastermind. Last time I spoke to her a year or two ago she was worried that they would never finish the work. The sheer volume of new laws and difficulty of consolidations seemed insurmountable. Would they ever have a complete image of current law?

I’ll start with a quote from one of the red-in-tooth-and-claw companies who are contributing to this.

I represent the Practical Law Company, one of the private sector organisations involved in the Expert Participation Programme. We’re really excited by these developments and salute John Sheridan and his team for their groundbreaking and elegant work on the API and legislation database. Legislation.gov.uk is the official publishing place for UK legislation and so it is really important work.

The programme is now starting to make a real and visible difference to the status of legislation on the website. By employing people to work with National Archives and as a first step, we’ve been able to ensure that the Companies Act 2006 is now fully consolidated on legislation.gov.uk. This is a particularly important piece of legislation for many of our customers but we intend to carry on the consolidation work on other legislation.

Well done, National Archives.

(Source: comment by Elizabeth Woodman)

Truly collaborative

The astonishing process goes roughly like this:

- John and Jeni and their team build an amazing web admin interface for skilled users to easily piece together the consolidated law jigsaw from the unconsolidated acts and statutory instruments.

-

Various organisations, such as the Practical Law Company, the Welsh Government (they want to sort out Welsh language law, nobody commercial can be bothered), the Department for Work and Pensions (they make legal guides for tens of thousands

of their staff, and so can’t afford the commercial providers) and a couple of other commercial providers (I’ll let John name names, as some that he mentioned to me aren’t fully announced yet) decided they want to contribute. -

They pay for some staff to work on it full time. The staff are trained initially by the National Archive, and work for the contributing organisation. There are currently about 30 in total. For example, Practical Law employ 14 people to do this stuff. There’s a queue, they can’t train new ones fast enough to meet demand.

-

The staff fix up the open data. It appears on legislation.gov.uk, as well as in XML files and as a SPARQL endpoint.

-

Profit. No really, this is a better business model than stealing underpants. For example, Practical Law release new products based on top of the now lovely clean, free data (such as the Companies Act they mention above).

The National Archive team were marking up 10,000 effects (i.e. patches of one bit of law over another) per year all by themselves. With 15,000 new effects being passed by Parliament each year, they were rapidly getting deeper into debt.

Now they’ve improved the process, and have the growning help of industry and other parts of Government, in just one year the basic metadata is done for it all. They aim to have fully caught up by 2015, including secondary legislation. Come the next Parliament, all laws should appear consolidated on the site – and anywhere else that wants it – in real time.

Saves money and improves lives

It’s win win win win. Well, unless you’re one of the two companies with a proprietary version of the database. Although they don’t seem too unhappy about it – for example, WestLaw has contributed electronic versions of pre-war Statutory Instruments that the Government had lost.

In the future there will be even more cost savings. For example, tens of millions are spent each year by the Court Service buying back proprietary copies of the laws they have to enforce. That could end when the open statute law database is fully finished in 2015.

However, as ever with public interest activity on the Internet, the real benefit is hidden and subtle. John explained to me that every month about 2 million people land on legislation.gov.uk after searching for things like “allotments act 1950” in search engines.

Most of them are non-lawyer professionals – HR, company secretaries, police officers. Better open legal data will help them do their job more effectively and in less time.

The next large user base is concerned citizens, defending their own rights. For example, a mother fighting with her local authority over statementing of her child. Giving them clear access to the law boosts their credibility with the authorities, and helps to make an otherwise messy dispute rules based and easier to resolve.

The lesson for open data projects

As well as being just brilliant, this story has torn a blindfold off a once baffled me. Why why why are there no collaborative open data curation projects?

Zarino Zappia, who works for my company ScraperWiki, did a whole thesis at the Oxford Internet Institute hunting for such projects. He couldn’t find any.

I now think the problem with the other nascent projects was that they didn’t include the upstream source (i.e. the National Archive in this case).

Upstream help in two ways:

- Act as a strong power to set up the project. It was both hard and expensive. In theory the Practical Law Company could have done this, but in practice the economic gain for just them wouldn’t have been enough.

-

The original source is being fixed. It’s hard to state how much better that is than tidying up a downstream copy (I know, from making

things like TheyWorkForYou and ScraperWiki). It’s technically and procedurally much less complicated. It gives a strong provenance and trust that simply cannot be earnt any other way.

Open source projects have different needs to get going. Open data curation is truly unique. You need both the data provider, and commercial contributors, for a sustainable project.

What data next?

I would like to see the same model applied to other open data sets. How about…

- Fine grained inflation data. Apparently somebody external offered to help the ONS improve the way they publish them, but were turned down. Perhaps now, with a successful example elsewhere in Government, this can happen.

-

Department for Transport data, such as public transport timetables. There’s some collaboration round this already, but would love to see the Government crowd sourcing accurate fixes so that the data becomes perfect (with Google, Apple, and FixMyTransport all contributing!).

-

Parliamentary debates. I know several organisations (some commercial, some charitable) who curate that data, which is increasingly a commodity. Parliament itself wants to publish it better. A project run between them all would be very powerful.

I’m sure you can think of many more.

And here’s the kicker. Jeni has has just been appointed Technical Director of The Open Data Institute. Where she is going to work out how to kickstart a flurry of such successful open data projects.

Today our law.

Tomorrow the world.

You can read more about this project here:

- John and Jeni’s slides from their talk at Strata, London 2012: Open Data: A New Tool for Government

- John’s blog post on the Cabinet Office digital service’s blog: Putting APIs first: legislation.gov.uk.

CEO of ScraperWiki. Made several of the world's first civic websites, such as TheyWorkForYou and WhatDoTheyKnow.

It’s good that there is more information available from Parliament, but all of this is a lot of work that could be avoided by the UK’s Parliament, and others, implementing Akoma Ntoso (a growing international standard for releasing legislation in XML) and switching from using Word to using CiviX Suite or Bungeni as their document rafter. These systems could be applied to all legislative, parliamentary, or any government documentation process.

The need to crowd source and scrape is nearly over— we’ve just got to make sure governments modernize their document drafting systems to automatically output in machine-readable formats.

Sarah – yes absolutely!

I know Parliament are talking to the National Archives – I’m sure they’re all trying to push this upstream, so initial tabling of motions happens straight in the structured system.

Not sure where they are on using Akoma Ntoso.