We’ve set out the basics of what open data means, so here we explore the Open Definition in more detail, including the importance of bulk access to open information, commercial use of open data, machine-readability, and what conditions can be imposed by a data provider.

Commercial Use

A key element of the definition is that commercial use of open data is allowed – there should be no restrictions on commercial or for-profit use of open data.

In the full Open Definition, this is included as “No Discrimination Against Fields of Endeavor — The license must not restrict anyone from making use of the work in a specific field of endeavor. For example, it may not restrict the work from being used in a business, or from being used for genetic research.”

The major intention of this clause is to prohibit license traps that prevent open material from being used commercially; we want commercial users to join our community, not feel excluded from it.

Examples of commercial open data business models

It may seem odd that companies can make money from open data. Business models in this area are still being invented and explored but here are a couple of options to help illustrate why commercial use is a vital aspect of openness.

You can use an open data set to create a high capacity, reliable API which others can access and build apps and websites with, and to charge for access to that API – as long as a free bulk download is also available. (An API is a way for different pieces of software or different computers to connect and exchange information; most applications and apps use APIs to access data via the internet, such as the latest news or maps or prices for products.)

Businesses can also offer services around data improvement and cleaning; for example, taking several sets of open data, combining them and enhancing them (by creating consistent naming for items within the data, say, or connecting two different datasets to generate new insights).

(Note that charging for data licensing is not an option here – charging for access to the data means it is not open data! This business model is often talked about in the context of personal information or datasets which have been compiled by a business. These are perfectly fine business models for data but they aren’t open data.)

Attribution, “Integrity” and Share-alike

Whilst the Open Definition permits very few conditions to be placed on how someone can use open data it does allow a few specific exceptions:

- Attribution: an open data provider may require attribution (. that you credit them in an appropriate way). This can be important in allowing open data providers to receive credit for their work, and for downstream users to know where data came from.

- Integrity: an open data provider may require that a user of the data makes it clear if the data has been changed. This can be very relevant for governments, for example, who wish to ensure that people do not claim data is official if it has been modified.

- Share-alike: an open data provider may impose a share-alike licence, requiring that any new datasets created using their data are also shared as open data.

Machine-readability and bulk access

Data can be provided in many ways, and this can have a significant impact on how easy it is to use it. The Open Definition requires that data be both machine-readable and available in “bulk” to help make sure it’s not too difficult to make useful.

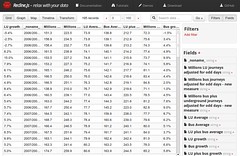

Data is machine-readable if it can be easily processed by a computer. This does not just mean that it’s digital, but that it is in a digital structure that is appropriate for the relevant processing. For example, consider a PDF document containing tables of data. These are digital, but computers will struggle to extract the information from the PDF (even though it is very human readable!). The equivalent tables in a format such as a spreadsheet would be machine-readable. Read more about machine-readability in the open data glossary.

Data is available in bulk if you can download or access the whole dataset easily. It is not available in bulk if you are you limited to just getting parts of the dataset, for example, if you are restricted to getting just a few elements of the data at a time – imagine for example trying to access a dataset of all the towns in the world one country at a time.

APIs versus Bulk

Providing data through an API is great – and often more convenient for many of the things one might want to do with data than bulk access, such as presenting some useful information in a mobile app.

However, the Open Definition requires bulk access rather than an API. There are two main reasons for this:

- Bulk access allows you to build an API (if you want to!). If you need all the data, using an API to get it can be difficult or inefficient. For example, think about Twitter: using their API to download all the tweets would be very hard and slow. Thus, bulk access is the only way to guarantee full access to the data for everyone. Once bulk access is available, anyone else can build an API which will help others use the data. You can also use bulk data to create interesting new things such as search indexes and complex visualisations.

- Bulk access is significantly cheaper than providing an API. Today you can store gigabytes of data for less than a dollar a month; but running even a basic API can cost much more, and running a proper API that supports high demand can be very expensive.

So having an API is not a requirement for data to be open – although of course it is great if one is available.

Moreover, it is perfectly fine for someone to charge for access to open data through an API – as long as they also provide the data for free in bulk. (Strictly speaking, the requirement isn’t that the bulk data is available for free but that the charge is no more than the extra cost of reproduction. For online downloads, that’s very close to free!) This makes sense: open data must be free but open data services (such as an API) can be charged for.

(It’s worth considering what this means for real-time data, where new information is being generated all the time, such as live traffic information. The answer here depends somewhat on the situation, but for open real-time data one would imagine a combination of bulk download access, and some way to get rapid or regular updates. For example, you might provide a stream of the latest updates which is available all the time, and a bulk download of a complete day’s data every night.)

Licensing and the public domain

Generally, when we want to know whether a dataset is legally open, we check to see whether it is available under an open licence (or that it’s in the public domain by means of a “dedication”).

However, it is important to note that it is not always clear whether there are any exclusive, intellectual-property-style rights in the data such as copyright or sui-generis database rights (for example, this may depend on your jurisdiction). You can read more about this complex issue in the Open Definition legal overview of rights in data. If there aren’t exclusive rights in the data, then it would automatically be in the public domain, and putting it online would be sufficient to make it open.

However, since, this is an area where things are not very clear, it is generally recommended to apply an appropriate open license – that way if there are exclusive rights you’ve licensed them and if there aren’t any rights you’ve not done any harm (the data was already in the public domain!).

More about openness coming soon

In coming days we’ll post more on the theme of explaining openness, including the relationship of the Open Definition to specific sets of principles for openness – such as the Sunlight Foundation’s 10 principles and Tim Berners-Lee’s 5 star system, why having a shared and agreed definition of open data is so important, and how one can go about “doing open data”.

Laura is CEO of the Open Knowledge Foundation, and Co-Founder and Director of Makespace. She has worked extensively in technology, innovation and leadership roles including at AT&T Labs, AlertMe.com and True Knowledge. Laura holds Masters and PhD degrees from the University of Cambridge, received the Royal Academy of Engineering Leadership Award and a NESTA Crucible Fellowship, and is a Chartered Engineer.

Maybe I’m jumping in here out of context but here goes …

This is a useful article on “open data”, but the title is misleading as it doesn’t really explore concepts of openness much at all. Openness is a term with great versatility & application but commentary that limits it to attributes of data or content in terms of licensing, intellectual property, access, &/or systems interoperability do not present anything like a whole or emerging contemporary picture. What about openness as transparent & due process? What about openness in activities like research, learning, inquiry, education, publishing, & scholarship etc? And philosophically, it’s ironic that licensing regimes are required to declare the degree of openness. We need more robust discourse about openness, otherwise its utility will diminish.