This blogpost was jointly written by Aleksi Knuutila and Georgia Panagiotidou. Their bio’s can be found at the bottom of the page.

In a recent blog post Tom Steinberg, long-term advocate of transparency and open data, looked back on what advocacy groups working on open government had achieved in the past decade. Overall, progress is disappointing. Freedom of Information laws are under threat in many countries, and for all the enthusiasm for open data, much of the information that is public interest remains closed. Public and official support for transparency might be at an all time high, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that governments are transparent.

Steinberg blames the poor progress on one vice of the advocacy groups: being excessively polite. In his interpretation, groups working on transparency, particularly in his native UK, have relied on collaborative, win-win solutions with public authorities. They had been “like a caged bear, tamed by a zookeeper through the feeding of endless tidbits and snacks”. Significant victories in transparency, however, always had associated losers. Meaningful information about institutions made public will have consequences for people in a position of power. That is why strong initiatives for transparency are rarely the result of “polite” efforts, of collaboration and persuasion. They happen when decision-makers face enough pressure to make transparency seem more attractive than any alternative.

The pressure for opening government information can result from transparency itself, especially when it is forced on government. Here the method with which information is made available matters a great deal. Metahaven, a Dutch design collective, coined the term black transparency for the situations in which disclosure happens in an uninvited or involuntary way. The exposed information may itself demonstrate how its systematic availability can be in the public interest. Yet what can be as revealing in black transparency is the response of the authorities, whose reactions in themselves can show their limited commitment to ideals of openness.

Over the past few years, a public struggle took place in Finland regarding information about who influences legislation. Open Knowledge Finland played a part in shifting the debate and agenda by managing to make public a part of the information in question. The story demonstrates both the value and limitations of opening up data as a method of advocacy.

Finland is not perfect after all

Despite its reputation for good governance, Finnish politics is exceptionally opaque when it comes to information about who wields influence in political decisions. In recent years lobbying has become more professional and increasingly happens through hired communications agencies. Large reforms, such as the overhaul of health care, have been mired by the revolving doors (many links in Finnish) between those who design the rules in government and the interest groups looking to exploit them. Yet lobbying in the country is essentially unregulated, and little information is available about who is consulted or how much different interest groups spend on lobbying. While regulating lobbying is a challenge – and transparency can remain toothless – for instance the European Commission keeps an open log about meetings with interest groups and requires them to publish information about their expenditure on lobbying.

Some mundane administrative records become surprisingly important in the public discussion about transparency. The Finnish parliament, like virtually any public building, keeps a log of people who enter and leave. These visitor logs are kept ostensibly for security and are not necessarily designed to be used for other purposes. Yet Finnish activists and journalists, associated with the NGO Open Ministry and the broadcaster Svenska Yle, seized these records to study the influence of private interests. After an initiative to reform copyright law was dropped by parliament in 2014, the group filed freedom of information requests to access the parliament’s visitor log, to see who had met with the MPs influential in the case. Parliament refused to release the information, and over two years of debate in courts followed. In December 2016 the supreme administrative court declared the records public.

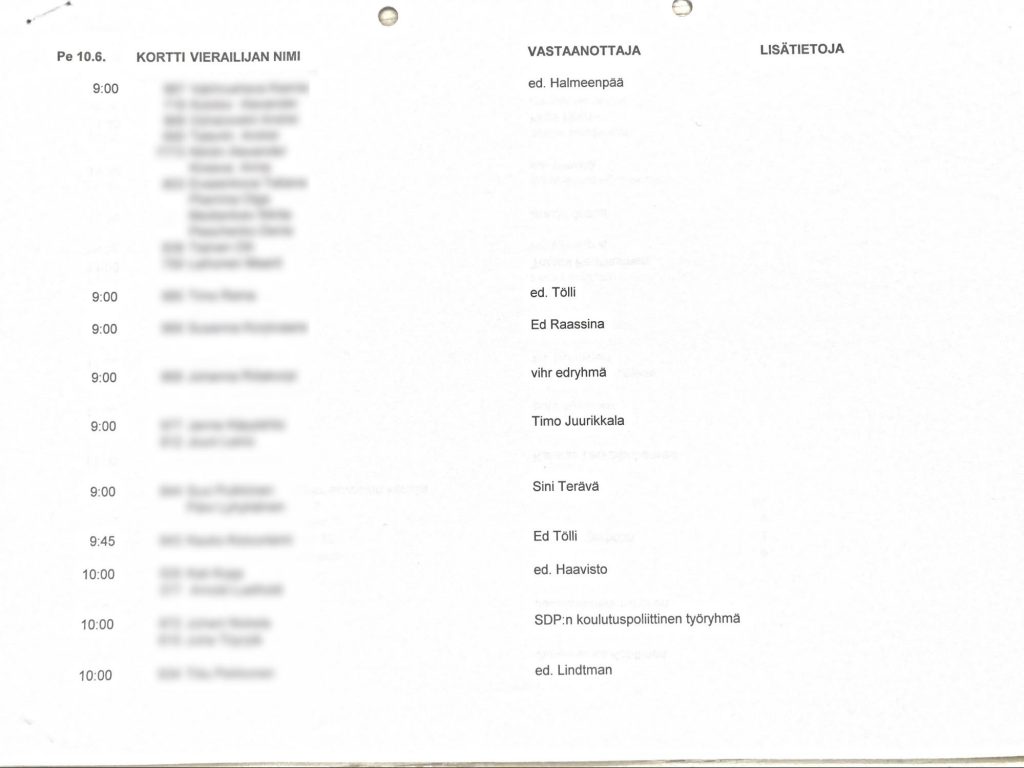

Despite the court’s decision, parliament still made access difficult. Following the judgment, the parliament administration began to delete the visitor log daily, making the most recent information about who MPs meet inaccessible. The court’s decision still forced them to keep an archive of older data. In apparent breach of law, the administration did not release this information in electronic format. When faced with requests for access to the records, parliament printed them on paper and insisted that people come to their office to view them. The situation was unusual: the institution responsible for legislation had also decided that it could choose not to follow the instructions of the courts that interpret law.

At this stage, Open Knowledge Finland secured the resources for a wider study of the parliament visitor logs. Because of the administration’s refusal to release the data electronically, we were uncertain what the best course of action was. Nobody knew what the content of the logs would be and whether going through them would be worth the effort. Still, we decided that we should collect and make the information available as soon as possible, while the archive that parliament kept still had some possible public relevance. Collecting and processing the data turned out to be a long process.

The hard work of turning documents into data

In the summer of 2017 the parliament’s administrative offices, on a side street behind the iconic main building, became familiar to us. After having our bags scanned in security, the staff would lead us to a meeting room. Two thick folders filled with papers had been placed on the table, containing the logs of all parliamentary meetings for a period of three months. We were always three people going to parliament, armed with cameras and staplers. After removing the staples from the printouts, we would take photographs in a carefully framed, standardised frame. To photograph the entire available archive, data from a complete year, required close to 2,000 images and four visits to the parliament offices.

Taking the photos in a carefully cropped way was important, since the next challenge was to turn these images into electronic format again. Only in this way could we have the data as a structured dataset that could be searched and queried. For this task open source tools proved invaluable. We used Tesseract for extracting the text from the images, and Tabula for making sure that the text was placed in structured tables. The process, so-called optical character recognition, was inevitably prone to errors. Some errors we were able to correct using tools such as OpenRefine, which is able to identify the likely mistakes in the dataset. Despite the corrections, we made sure the dataset includes references to the original photos, so that the digitised content could be verified from them.

Transforming the paper documents into a useable database required roughly one month of full-time work, spread between our team members. Yet this was only the first step. The content of the visitor log itself was fairly sparse, in most cases only containing dates and names, and little information about people’s affiliations, let alone the content of their meetings. To refine it, we scraped the parliament’s website and connected the names that occur in the log with the identities and affiliations of members of parliament and party staff. Using simple crowdsourcing techniques and public sources of information, we looked at a sample of the 500 people that most frequently visited parliament and tried to understand who they were working for. This stage of refinement required some tricky editorial choices, determining which questions we wanted the data to answer. We chose for instance to classify the most frequent visitors, to be able to answer questions about what parties are most frequently connected to particular types of visitors.

Collaboration with the media

For data geeks like us, being able to access this information was exciting enough. Yet for our final goal, making a case for better regulation on lobbying, releasing a dataset was not sufficient. We chose to partner with investigative journalists, who would be able to present, verify and contextualise the information to a broader audience. Our own analytical efforts focused broader patterns and regularities in the data, while journalists who have been covering Finnish politics for a long time were able to find the most relevant facts and narratives from the data. We gave the data under an embargo to some key journalists, so they would have the time and resources to work on the information. Afterwards the data was available to all journalists who requested it for their own work.

We were lucky that there was sustained media interest in the information. Alfred Harmsworth, the founder of the Daily Mirror, is attributed with the quote “news is what somebody somewhere wants to suppress; the rest is advertising”. In the same vein, when the story broke that the Finnish parliament had started deleting the most recent data about visitors, the interest in the historical records was guaranteed.

Despite the heightened interest, we also became conscious of how difficult it was for the media to interpret data. This was not just because of a lack of technical skills. There simply was such a significant amount of information – details of about 25,000 visits to parliament – that isolating the most meaningful pieces of information or getting an overview of what had happened was a challenge. For news organisations, for whom the dedication of staff even for days on a topic was a significant undertaking, investing into this kind of research was a risk. Even if they would spend the time going through the data, the returns of doing this were uncertain and unclear.

After we released the data to a wider range of publications, many news outlets ended up running fairly superficial stories based on the data, focusing on for instance the most frequently occurring names and other quantities, instead of going through the investigative effort of interrogating the significance of the meetings described in the logs. Information that is in the form of lists lends itself easily to clickbait-like titles. For media outlets that could not wait for their competition to beat them to it, this was to be expected. The news coverage was probably weakened by the fact that we could not share the data with a broader public, due to the fact that it contained personal details that were potentially sensitive. For instance Naomi Colvin has suggested that searchable public databases, that open information for wider scrutiny and discovery, can help to beat the fast tempo of the news cycle and maintain the relevance of datasets.

The stories that resulted from the data

What did journalists find when they wrote stories based on the data? Suomen Kuvalehti ran an in-depth feature that included investigations into the private companies that were most active lobbying. These included a Russian-backed payday loans provider as well as Uber, whose well-funded efforts extend even to Finland. YLE, the Finnish public broadcaster, described the privileged access that representatives of nuclear power enjoyed, while the newspaper Aamulehti showed how individual meetings between legislators and the finance industry had managed to shift regulation. Our own study of the data showed how representatives of private industry were more likely to have access to parties of the governing coalition, while unions and NGOs met more often with opposition parties.

In essence, the stories provided detail about how well-resourced actors were best placed to influence legislation. It confirmed, a cynical person might note, what most people had thought to be the case in the first place. Yet having clear documentation of this phenomenon may well make it harder to ignore. This line of argumentation was often raised with recent large leaks, the value of which may not lie in making public new facts, but providing the concrete data that makes the issue impossible to ignore. “From now on, we can’t pretend we don’t know”, as Slavoj Zizek ironically noted on Wikileaks.

Overall the media response was large. According to our media tracking, at least 50 articles were written in response to the release of the data. Several national newspapers ran editorials on the need for establishing rules for lobbying. In response, four political parties, out of the eight represented in parliament, declared that they would start publishing their own meetings with lobbyists. Parliament was forced to concede, and began to release daily snapshots of data about meetings in an electronic format. These were significant victories, both in practices of transparency as well as changing the policy agenda.

On the importance of time and resources

For a small NGO such as ours, the digitising and processing of information on this scale would obviously not have been possible recently, perhaps even five years ago. Our work was expedited by the availability of powerful open source tools for difficult tasks such as optical character recognition and correcting errors. Being a small association had its advantages as well, as we were aided by the network around the organisation, from which we were able to draw volunteers in areas from data science to media strategy. In many cases governments contain the consequences of releasing information through a kind of excess of transparency: they release so many documents, often in formats that are hard to process, that their meaning becomes muddled. When documents can be automatically processed and queried, this strategy weakens.

Still, it would be naive to think that technology is enough to make information advocacy effective or enough to allow everybody to participate in it. This line of work was possible due to some people’s commitment and personal sacrifice that spanned several years, as well as significant amounts of funding on the right moments. Notably, no newsroom would by themselves have had the resources to sustain the several months of labour that working through the data required. The strategy of being less “polite”, in Tom Steinberg’s terms, may well be desirable, but the obvious challenge is securing the resources to do it.

Author bio’s

Dr. Aleksi Knuutila is a social scientist with a focus on civic technologies and the politics of data, and an interest in applying both computational and qualitative methods for investigation and research. As a researcher with Open Knowledge Finland, he has advised the Finnish government on their personal data strategy and studied political lobbying using public sources of data. He is currently working on an a toolkit for using freedom of information for investigating how data and analytics are used in the public sector.

Georgia Panagiotidou is a software developer and data visualisation designer, with a focus on the intersections between media and technology. She was part of the Helsingin Sanomat data desk where she used to work to make data stories more reader friendly. Now, among other things, she works in data journalism projects most recently with Open Knowledge Finland to digitise and analyse the Finnish parliament visitor’s log. Her interests lie in open data, civic tech, data journalism and media art.

We would like to thank the following people who gave an invaluable contribution to the work: Sneha Das, Jari Hanska, Antti Knuutila, Erkka Laitinen, Juuso Parkkinen, Tuomas Peltomäki, Aleksi Romanov, Liisi Soroush, Salla Thure

Dr Aleksi Knuutila is a social scientist with a focus on civic technologies and the politics of data, and an interest in applying both computational and qualitative methods for investigation and research. As a researcher with Open Knowledge Finland, he has advised the Finnish government on their personal data strategy and studied political lobbying using public sources of data. He is currently working on an a toolkit for using freedom of information for investigating how data and analytics are used in the public sector.