Findings from the Africa Open Data Index and Africa Data Revolution Report

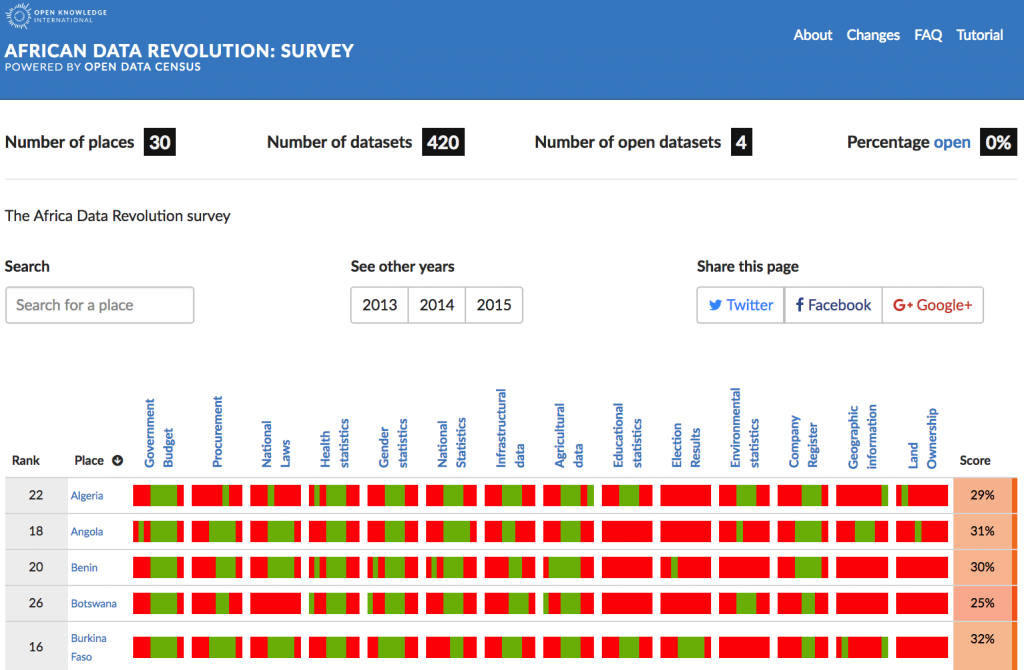

Today, we are pleased to announce the results of Open Knowledge International’s Africa Open Data Index. This regional version of our Global Open Data Index collected baseline data on open data publication in 30 African countries to provide input for the second Africa Data Revolution Report.

Based on an adaptation of the methodology for the Global Open Data Index, this project mapped out to what extent African public institutions make key datasets available as open data online. Beyond scrutinising data availability, digitisation degree, and openness of national datasets, we considered the broader landscape of actors involved in the production of government data such as private actors.

Key datasets and methodology were developed in collaboration with the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), the International Development Research Centre (IDRC), and well as the World Wide Web Foundation. We focused on national key datasets such as:

- Data describing processes of government bodies at the highest administrative level (e.g. federal government budgets);

- Data produced by sub-national actors but collected by a national agency (e.g. certain statistical information).

We also captured if data was available on sub-national levels or by private companies but did not assign scores to these sets. You can find the detailed methodology here.

Ultimately, the key datasets we considered are:

- Administrative records: budgets, procurement information, company registers

- Legislative data: national law

- Statistical data: core economic statistics, health, gender, educational and environmental statistics

- Infrastructural data

- Agricultural data

- Election results

- Geographic information and land ownership

Understanding who produces government data

Many government agencies produce at least parts of the key datasets we assessed. Some key datasets, such as environmental data, are rarely produced. For instance, air pollution and water quality data are sometimes produced in individual administrative zones, but not on national levels. Some initiatives assist producing data on deforestation, such as REDD+ or the Congo Basin Forest Atlases, with the assistance of the World Resources Institute (WRI) and USAID.

Multiple search strategies may be required to identify agencies producing and publishing official records. Some agencies develop public databases, search interfaces and other dedicated infrastructure to facilitate search and retrieval. Statistical yearbooks are another useful access point to several information groups, including economic and social statistics as well as figures on environmental degradation or market figures. In several cases it was necessary to consult third-party literature to identify which public institutions hold the remits to collect data such as World Bank’s Land Governance Assessment Framework (LGAF) and reports issued by the Extractives Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI).

Sometimes, private companies provide data infrastructure to aggregate and host data centrally. For instance, the company Trimble develops data portals for the extractives sector in 15 countries in Africa. These data portals are used to publish data on mining concession, including geographic boundaries, the size of territory, concession types, licensees, or contract start and duration.

Procuring data infrastructure from private organisations

While being a useful central access point, Trimble’s terms of use do not comply with open licensing requirements. This points to a larger concern regarding appropriate licensing schemes and how they can be integrated into the procurement process. We propose that multi stakeholder initiatives such as the Extractives Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) and national multi stakeholder groups define appropriate terms of use, recommending the use of standard open licences, when procuring services in order to ensure an appropriate degree of openness to prevent lock-in and public access.

An alternative information aggregator using open licence terms is called African Legal Information Institute (AfricanLII), gathering national legal code from several African countries. It is a programme of the Democratic Governance and Rights Unit at the Department of Public Law at the University of Cape Town.

Sometimes stark differences what data gets published

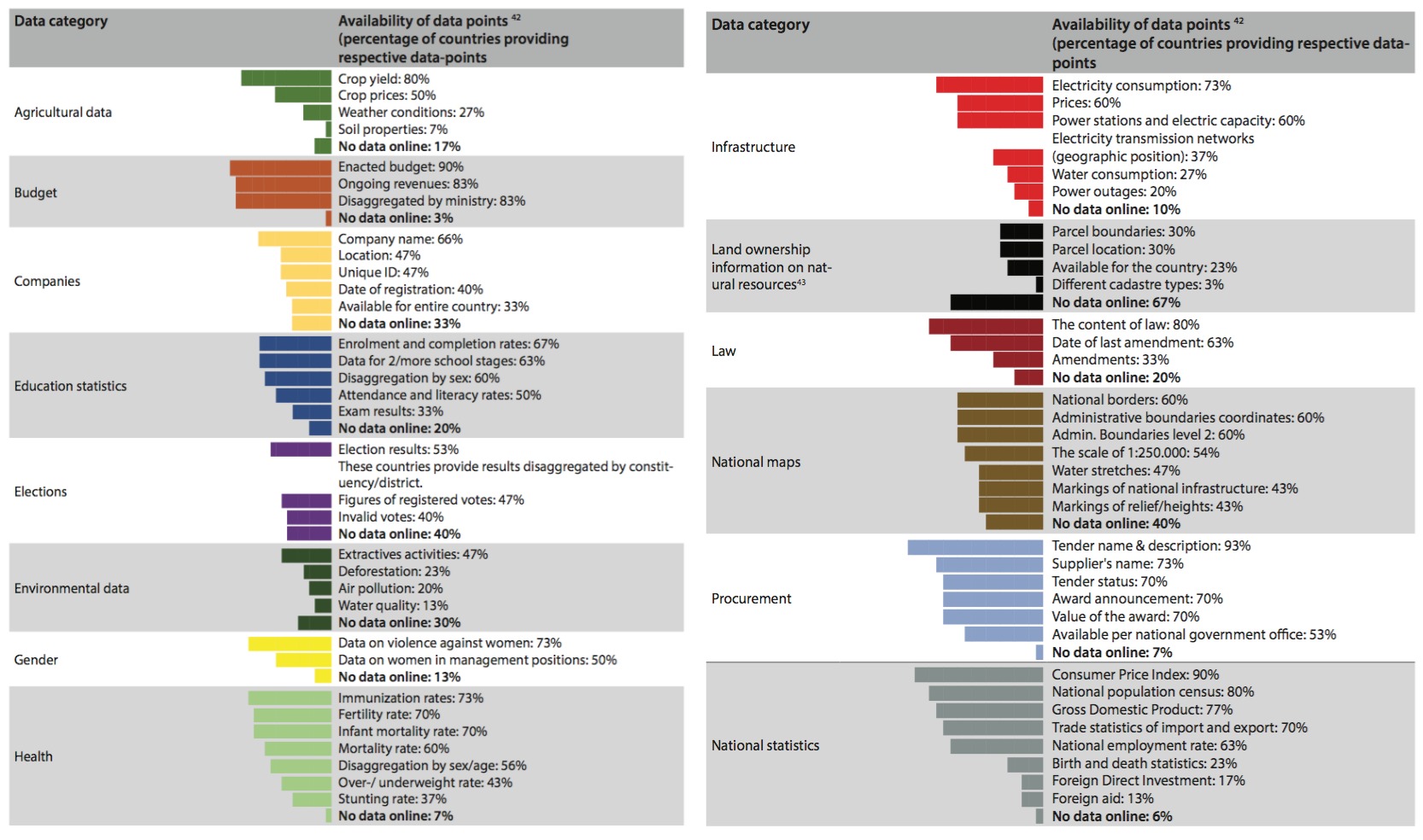

To test what data gets published online, we defined crucial data points to be included in every key data category (see here). If at least one of these data points was found online, we considered the data category for assessment. This means that we assessed datasets whose completeness can differ across countries. Figure 2 shows which data points are how often provided across our sample of 30 countries.

Budget and procurement data most often contains the relevant data points we have assessed. Several key statistical indicators are provided fairly commonly, too. Agricultural data, environmental data and land ownership data are least commonly provided. For a more thorough analysis we recommend to read the Africa Data Revolution Report, pages 16-22.

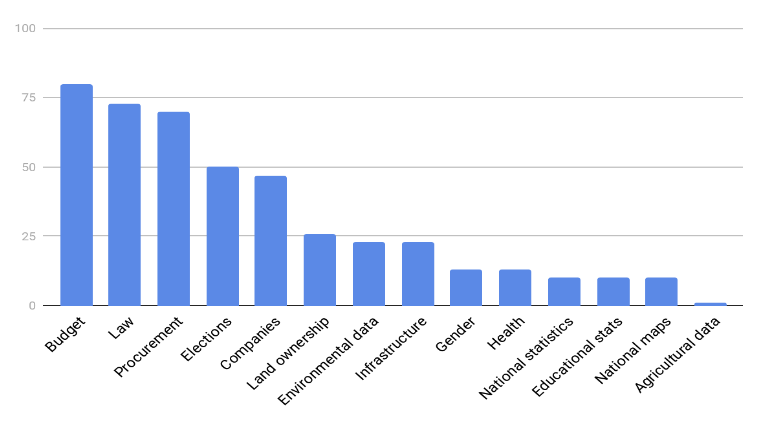

One third of the data is provided in a timely manner

To assess timely publication our research considered whether governments publish data in a particular update frequency. Figure 3 shows a clear difference in timely data provision across different data types. The y-scale indicates the percentage of countries publishing updated information. A score of 100 would indicate that the total sample of 30 countries publishes a data category in a timely fashion.

We found significant differences across individual data categories and countries. Roughly three out of four countries update their budget data (80% of all countries), national laws (73% of all countries) and procurement information (70% of all countries) in a timely manner. Approximately half of all countries publish updated elections records (50% of all countries), or keep their company registers up-to-date (47% of all countries). All other data categories are published in a timely manner only by a fraction of the assessed countries. For instance, the majority of all countries does not provide updated statistical information.

We strongly advise to interpret these findings as trends rather than representative representations of timely data publication. This has several reasons. In some data categories, we included considerably more and diverse data points. For instance, the agricultural data category includes not only statistics on crop yields but also short-term weather forecasts. If one of these data types was not provided in a timely manner, the data category was considered not to be updated. Furthermore, if a country did not provide timestamps and metadata, we did not consider the data to be updated, as we were unable to proof the opposite.

Open licensing and machine-readability

Only 6% of all data (28 out of 420 datasets assessed) is openly licensed in compliance with the criteria laid out by the Open Definition. Open licence terms are used by statistical offices in Botswana, Senegal, Rwanda, and Somalia, as well as open data portals in Cote d’Ivoire, Eritrea and Kenya and Mauritius. Usually, websites provide copyright notes but do not apply licence terms dedicated to the website’s data. In rare cases we found a Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) licence being used. More common are bespoke terms that are compliant with the Open Definition.

14.5% of all data (61 out of 420 datasets assessed) is provided in at least one machine-readable format. Most data, however, is provided in printed reports, digitised as PDFs, or embedded on websites in HTML. Importantly, some types of data, such as land records, may still be in the process of digitisation. If we found that governments hold paper-based records, we tested if our researchers may request the data. If this was not the case, we did not consider the data for our assessment.

Recommendations

The following recommendations are excerpts from the Africa Data Revolution Report 2018. A comprehensive list of recommendations can be found in the report itself.

On the basis of our findings we recommend that public institutions:

- Communicate clearly on their agency websites what data they are collecting about different government activities.

- Clarify which data has authoritative status in case multiple versions exist: Metadata must be available clarifying provenance and authoritative status of data. This is important in cases where multiple entities collect data, or whenever governments gather data with the help of international organisations, bilateral donors, foreign governments, or others.

- Make data permanently accessible and findable: Data should be made available at a permanent internet location and in a stable data format for as long as possible. Avoid broken links and provide links to the data whenever you publish data elsewhere (for example via a statistical agency). Add metadata to ensure that data can be understood by citizens and found via search engines.

- When procuring data, define a set of terms of use to ensure the appropriate degree of openness: Private vendors may want to license data under proprietary terms, which may limit data accessibility. Research found that many data-intense projects in development contexts use haphazard, proprietary licence terms which may prevent the public from accessing data, increase complexity of use terms, and costs of data access.

- Provide data in machine-readable formats: Ensure that data is processable. Raw data must be published in machine-readable formats that are user friendly.

- Use standard open licences: Use CC0 for public domain dedication or standardized open licences, preferably CC BY 4.0. They can be reused by anyone, which helps ensure compatibility with other datasets. Clarify if data falls under the scope of copyright, or similar rights. If information is in the public domain, apply legally non-binding notices to your data. If you opt for a custom open licence, ensure compatibility with the Open Definition. It is strongly recommended to submit the licence for approval under the Open Definition.

- Avoid confusion around licence terms: Attach the licence clearly to the information to which it applies. Clearly separate a website’s terms and conditions from the terms of open licences. Maintain stable links to licences so that users can access licence terms at all times.

More information

We have gathered all raw data in a summary spreadsheet. Browse the results and use the links we provide to reach a dataset of interest directly.

If you are interested in specific country assessments, please find here our research diaries.

The Open Data Survey tool, powering this project as well as our Global Open Data Index is open to be reused. If you are interested in setting up a regional or national version, get in touch with us at index@okfn.org.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the experts at Local Development Research Institute (LDRI), the Communauté Afrique Francophone pour les Données Ouvertes (CAFDO) and the Access to Knowledge for Development Center (A2K4D) at the American University, Cairo for advising on the methodology and their support throughout the research process. Furthermore, we would like to thank our 30 country researchers, as well as our expert reviewers Codrina Maria Ilie, Jennifer Walker, and Oscar Montiel. Finally, we would like to thank our partners at the United Nations Development Programme, the International Development Research Centre and the Web Foundation, without whose support this project would not have been possible.

Danny Lämmerhirt works on the politics of data, sociology of quantification, metrics and policy, data ethnography, collaborative data, data governance, as well as data activism. You can follow his work on Twitter at @danlammerhirt. He was research coordinator at Open Knowledge Foundation.