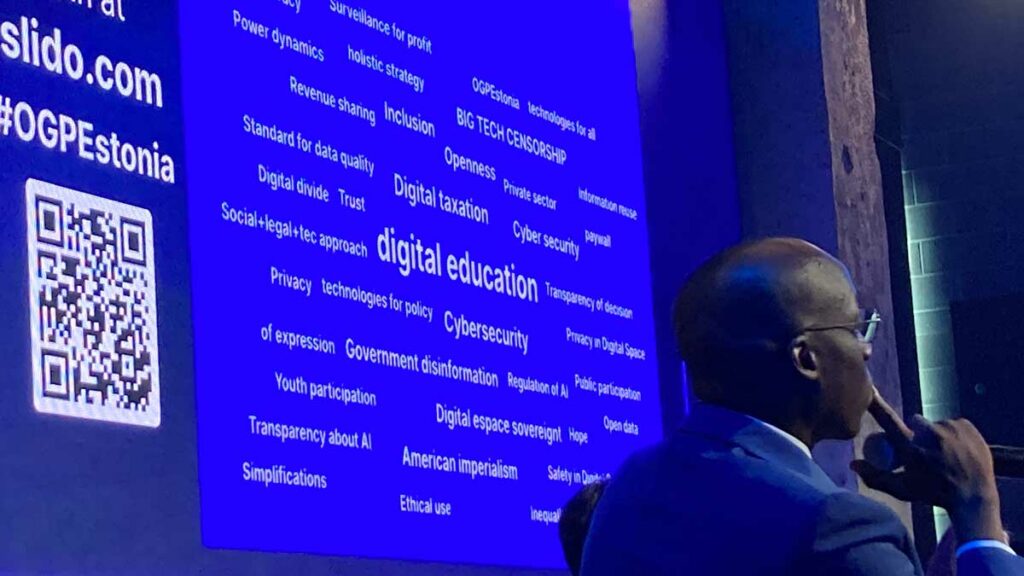

I have been working actively opening governments with my technical skills and social organising since 2013 locally, in Córdoba, Argentina, but this was the first time I had the opportunity to interact with the broader ecosystem in Tallinn, Estonia, during the last Open Government Partnership (OGP) Global Summit.

A frequently asked question I received there is if there can be an open government without any political will from the government. I say the same thing here as I said in the panel “Openness as a Design Principle”, part of the side event promoted by the Open Knowledge Foundation (check out the photos): the simple answer is no, it cannot. But it is important to understand open government as a broader concept, more than just “governments opening their data”.

More importantly, open government should not be understood as a unilateral action made by the government to the society but rather as a multi-directional flow between the different stakeholders in a democracy.

As a long-life activist, I define open government as “a democratic tool that political parties, civil society, and other actors of a democracy use to push their agendas”. I have never experienced nor seen a pure “open government” where information is openly shared just for the sake of doing good. Open government is commonly seen in practice as a power dynamic inside democracies, where each actor will use it or ignore it to consolidate its position and influence in the society.

But we also must be aware that an open government strategy can be a way to advance a country’s agenda without any conflict between words and practice. For instance, while former US President Barack Obama signed an executive order ten years ago that made open and machine-readable data the new default for government information, his administration was the one prosecuting the largest number of whistleblowers and journalists using anachronic laws.

Today, as we gather to evaluate the government’s commitments to openness and transparency, Julian Assange is still being tortured in pre-trial detention, prosecuted for revealing war crimes and unveiling state criminality.

It’s time to move out from the overused excuse of “national security”, as the Estonian Prime Minister Kaja Kallas said in the opening speech: ”History has seen authoritarians destroy democracies, often by destroying individual rights and excusing it with “protecting” national security and economy.” Being truly open about our war data, including the number of casualties, vendors, resources devoted to it, and the evidence of potential war crimes, is even more important when the main propaganda against democratic states is based on how much hypocrisy there is in our governments.

We should start practicing what we preach. How is it possible to condemn war crimes with integrity while democracies imprison citizens for revealing them? How can we say we are opening governments while classifying information about war crimes perpetrated by our governments? To quote again the Prime Minister of Estonia: “How can we make sure that openness is understood as a strength, not a weakness?”

From words to meaningful actions

I have a suggestion: start opening classified historical documents, especially those related to state and war crimes. The relatives of victims of summary executions, enforced disappearance, missing persons, abducted children, and torture need to know what happened to them as soon as possible. For example, only now is the US declassifying relevant documents of this nature related to the 1973 coup in Chile, fifty years after the events, when many of the victims and perpetrators already passed away. Too little, too late.

During OGP Estonia, it was several times stated that democracy is at its tipping point. If so, we need to strongly show that we are different, brave and mature enough to openly face our mistakes. There is no more human and powerful response to authoritarian propaganda than showing them how humane we are.

Beyond FOIA, we need whistleblowers

At this point, it is clear that there are well-defined limits when we are talking about open government. Governments won’t embrace an open initiative if it goes too deep into the secrets of power. While producing innovation and collaboration, open government will fail to be a tool to disclose state criminality and lead to accountability. “What about FOIA (Freedom Of Information Acts)?”, some will ask. But the answer is still quite similar: there is no viable vehicle to exercise the right to access public information when journalists need to pay thousands of dollars in litigation fees and wait years to obtain the documents. So, in conclusion, without more whistleblowers exposing state criminality and more laws and tools to protect them, there will never be an open government.

My wishes for the next OGP in 2025: more journalists talking about their experiences using FOIA, more activists showing their struggles in the front line of the social fights, and a free Julian Assange.