The following guest post is by Charles Armstrong, social scientist, entrepreneur, and Founder of the One Click Orgs project, which the OKF supports. Charles will be joining us at OKCon2011 for his talk, One Click Orgs: simple democratic organisation

Along the shoreline of the North Atlantic marram grass plays a vital role in the coastal ecosystem. Its tough root networks enable it to stabilise shifting sand dunes and create conditions where a broader ecology can start to develop. It is tempting to see the role that clubs, associations and cooperatives play in society in a similar light. They forge durable networks of trust and shared interest which bind people together and help to stabilise the ever-shifting ferment of society, laying the ground for other kinds of collaboration to flourish.

Photo: Kieran Campbell. CC-BY-SA.

Civil society organisations possess two qualities which are particularly useful from this perspective. First, they are formally constituted. A loose informal collaboration is likely to have a markedly different impact from the same set of people collaborating as a constituted organisation. The process of creating an organisation propagates a fixed consciousness of shared identity and purpose which subtly alters the perspective of members and the outside world. A constitution provides a set of rules and processes which structure the collaboration and increase the members’ ability to achieve their objectives. Forming an organisation gives birth to an enduring entity which may outlive every one of its original members.

Second, civil society organisations are democratic. The vast majority are structured to be governed collectively by their members. In some cases decisions are voted on directly by all a group’s members. In other cases members elect officers or a representative committee to make day to day decisions. But either way a member who feels strongly about some aspect of what the organisation is doing has ways to control the choices that are made. The importance of these small-scale democracies is inestimable. Civil society organisations provide a setting where people can increase their literacy in democratic participation, focused on issues and decisions which directly concern them. There is no better nursery for active and effective involvement in the larger democracies of cities and nations.

A thriving ecosystem of civil society organisations has been recognised as an essential part of a healthy society since at least the eighteenth century. But it is arguably more important now than in any previous period. Throughout the rich world states are scaling back social services at the same time as local resources such as schools, shops, post offices and pubs are disappearing. In many cases the best hope of filling the gaps is for citizen groups to come together and form local organisations to take over provision of vital services. In the UK this approach is openly advocated by the government’s Big Society initiative. But the challenges facing communities trying to form effective organisations and draw in people to sustain them are formidable.

At the same time the poor world is being swept by a quite different wave of change. A growing number of authoritarian regimes are waking up to find citizen groups organising themselves to press demands for democratic reform. Many of these societies have little or no civil society infrastructure. Turning the anger and idealism of citizen uprisings into sustainable democratic fabric requires an ecosystem of civil society organisations to spring up and take root a hundred times faster than happened in Western Europe or the USA.

These circumstances throw a spotlight on the factors which inhibit the formation of civil society organisations or participation in them. Under this spotlight two barriers stand out in particular. The complexity of forming an organisation, and the effort required to sustain active involvement.

On the first point, anyone contemplating setting up a new organisation is faced with a bewildering variety of different legal structures, for each of which a multitude of different constitutions is available. Founders typically go through a crash course to educate themselves on the arcana of corporate law, contract law and charity law. The result is fewer organisations being formed and too many organisations being created with an off-the-shelf structure which fits their needs poorly.

On the second point, once an organisation is formed anyone who wants to be an active participant in shaping its direction must be prepared to attend meetings, study agendas and minutes, get their head around voting procedures and know how to table resolutions in the proper fashion. Not surprisingly this discourages an awful lot of people from getting involved, even if they strongly support a group’s objectives.

In the past little attention has been paid to these two barriers because, well, that’s just how it was. However, just at the moment a dramatic increase in new organisation formation and participation is needed most urgently, an innovation has appeared which makes it possible. The internet has already triggered revolutions in countless complex processes such as airline reservations, organising auctions and filing tax returns. Now organisational structures are being reinvented to take advantage of the internet’s capacity for instantaneous communication, automation and complex many-to-many interaction. Say hallo to the virtual organisation.

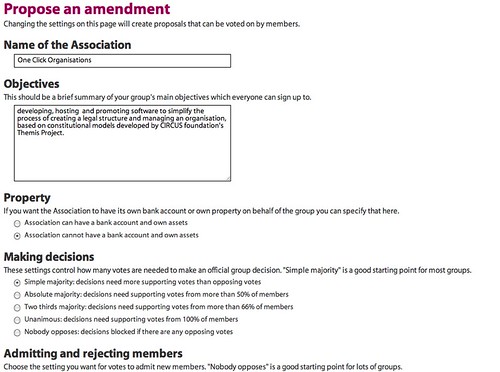

From a legal perspective virtual organisations are no different from traditional ones. They maintain all the outside characteristics of established structures such as cooperatives, corporations or partnerships. But whilst the exterior form remains the same most of what lies under the skin is re-engineered. In a virtual organisation the constitution is welded onto an electronic system which automates all the logic governing membership, board appointments, voting and constitutional amendments. One result of this automation is that processes which previously required meetings or written resolutions can now happen online with the system taking care of all the bureaucratic tedium.

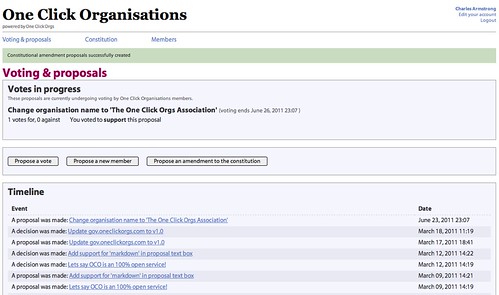

The experience of participating in a virtual organisation resembles many familiar web activities. Founding an organisation is like creating an email group. Proposing a resolution is similar to posting on a forum. Voting is like responding to an online poll. Proposing an amendment to the constitution is no more complex then changing the moderation settings on a blog (triggering an automatic vote to authorise it).

Different jurisdictions vary enormously in their openness to virtual organisations. Currently two of the most favourable are the State of Vermont, which in 2008 reformed its corporation law with this specific objective, and the UK, whose 2006 Companies Act achieved the same end largely by accident. It is perhaps no coincidence that the two initiatives which have pioneered the development of virtual organisations are the Digital LLC project at Harvard University’s Berkman Centre, led by Oliver Goodenough – who happens to be Professor at Vermont Law School; and One Click Orgs, an open source project based in London (which I helped set up).

Whilst the Harvard project is working to virtualise profit-making corporations One Click Orgs has focused on the opportunities for civil society. In March 2011 the project launched a website (oneclickorgs.com) where community groups can create an unincorporated association and the tools to run it, completely free of charge. If you’re interested you can go there, right now, and set up your own association. It’s a 100% Open Service so you’re also free to reuse and adapt the code and constitutions.

The One Click Orgs platform generates a constitution which most banks will accept to open a shared account, a simple voting system for group decisions, a record of resolutions the group has passed and an official list of members who have been voted in. One Click Orgs is also working with London Hackspace to create a virtualised platform for Companies Limited by Guarantee, the UK equivalent of a non-profit corporation. Finally it has just started scouting for funders to support development of a platform for Industrial and Provident Societies, recently rebranded as Community Benefit Societies. These are the ideal structures for community groups to take on the running of local facilities and services such as post offices, shops and village halls.

From an open knowledge perspective virtual organisations are significant because they represent a radical increase in transparency around an organisation’s constitution and governance processes. Few members of traditional community associations or non-profits ever actually read their group’s constitution or think about how it could be improved. With a virtual organisation everything is visible and malleable, helping members participate effectively and increasing the chance the organisation will be able to evolve over time and continue to advance its objectives.

Virtual organisations have all kinds of other interesting implications. The time is not far away when email groups and World of Warcraft guilds will be able to incorporate themselves, sell shares and enter into contracts with each other. Approaches to investment are also liable to change dramatically as a fusion of virtual organisations and crowdfunding offers the capacity to tie investment to direct participation in decisions, potentially scaling to millions of shareholders. Eventually the governance of nation states is bound to be affected by these new possibilities, which I have explored a little in my writings on Emergent Democracy. But these speculations belong in a different article.

In the meantime I would urge anyone working to increase civil society capacity to start looking for ways to enable virtual organisations in the part of the world where they’re active. There is still a lot of work to do to update legal frameworks in more conservative jurisdictions (California is notably backward). But if that leads to a doubling or tripling of the rate at which new organisations are created, and a similar increase in levels of citizen participation, the effort will seem trivial in comparison to the benefits for society.

It is as if, just at the moment one’s village is about to be swamped by sand dunes, a new variety of marram grass is discovered which grows twenty times faster than the old stock. It’s time to get planting.

Theodora is press officer at the Open Knowledge Foundation, based in London. Get in touch via press@okfn.org