In 2010, I had a long paper about the history of German translations of Othello rejected by a prestigious journal. The reviewer wrote: “The Shakespeare Industry doesn’t need more information about world Shakespeare. We need navigational aids.”

About the same time, David Berry turned me on to Digital Humanities. I got a team together (credits) and we’ve built some cool new tools.

All culturally important works are translated over and over again. The differences are interesting. Different versions of Othello reflect changing, contested ideas about race, gender and sexuality, political power, and so on, over the

centuries, right up to the present day. Hence any one translation is just one snapshot from its local place and moment in time, just one

interpretation, and what’s interesting and productive is the variation, the diversity.

But with print culture tools, you need a superhuman memory, a huge desk and ideally several assistants, to leaf backwards and forwards in all the copies, so you can compare and contrast. And when you present your findings, the minutiae of differences can be boring, and your findings can’t be verified. How do you know I haven’t just picked quotations that support my argument?

But with digital tools, multiple translations become material people can easily work and play with, research and create with, and we can begin to use them in totally new ways.

##Recent work

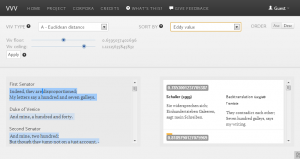

We’ve had funding from UK research councils and Swansea University to digitize 37 German versions of Othello (1766-2010) and build these prototype tools. There you can try out our purpose-built database and tools for freely segmenting and aligning multiple versions; our timemap of versions; our parallel text navigation tool which uses aligned segment attributes for navigation; and most innovative of all: the tool we call ‘Eddy and Viv’. This lets you compare all the different translations of any

segment (with help from machine translation), and it also lets you read the whole translated text in a new way, though the variety of translations. You don’t need to know the translating language.

This is a radical new idea (more details on our platform). Eddy and Viv are algorithms: Eddy calculates how much each translation of each segment differs in wording from others, then Viv maps the variation in the results of that analysis back onto the translated text segments.

This means you can now read Shakespeare in English, while seeing how much all the translators disagree about how to interpret each speech or line, or even each word. It’s a new way of reading a literary work through translators’ collective eyes, identifying hotspots of

variation. And you don’t have to be a linguist.

##Future plans and possible application to collections of public domain texts

<img src=”http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/70/Arthur_Rackham_Little_Red_Riding_Hood%2B.jpg/405px-Arthur_Rackham_Little_Red_Riding_Hood%2B.jpg” width=162″ height=”240″ align=”left” />

I am a linguist, so I’m interested in finding new ways to overcome language barriers, but equally I’m interested in getting people interested in learning languages. Eddy and Viv have that double effect. So these are not just research tools: we want to make a cultural difference.

We’re applying for further funding. We envisage an open library of versions of all sorts of works, and a toolsuite supporting experimental and collaborative approaches to understanding the differences, using visualizations for navigation, exploration and

comparison, and creating presentations for research and education.

The tools will work with any languages, any kinds of text. The scope is vast, from fairy tales to philosophical classics. You can also investigate versions in just one language – say, different editions of an encyclopedia, or different versions of a song lyric. It should be possible to push the approach beyond text, to audio and video, too.

Shakespeare is a good starting point, because the translations are so numerous, increasing all the time, and the differences are so intriguing. But a few people have started testing our tools on other materials, such as Jan Rybicki with

Polish translations of Joseph Conrad’s work. If we can demonstrate the value, and simplify

the tasks involved, people will start on other ‘great works’ – Aristotle, Buddhist scripture,

Confucius, Dante (as in Caroline Bergvall’s amazing sound work ‘Via’), Dostoyevski,

Dumas…

Many translations of transculturally important works are in the public domain. Most are

not, yet. So copyright is a key issue for us. We hope that as the project grows,

more copyright owners will be willing to grant more access. And of course

we support reducing copyright restrictions.

Tim Hutchings, who works on digital scriptures, asked me recently: “Would it be possible

to create a platform that allowed non-linguist readers to appreciate the differences in tone

and meaning between versions in different languages? … without needing to be fluent in

all of those languages.” – Why not, with imaginative combinations of various digital tools

for machine translation, linguistic analysis, sentiment analysis, visualization and not least:

connecting people.

Tom Cheesman is Reader in German at the University of Swansea. He is the Principal Investigator on the collaborative, multi-disciplinary ‘Version Variation Visualisation’ project, looking at Digital Humanities approaches to analysing the multiplicity of Shakespeare re-translations.