This week eight of the world’s most powerful nations made unprecedented multilateral commitments to open up their data:

- the Open Data Charter says that that public information should be published in accordance with open data principles by default;

- the Lough Erne Declaration emphasises the importance of increased transparency in cracking down on tax evasion, corruption and illegal or unfair practises in natural resource extraction and land transactions.

But while “pollution levels” gets a cursory mention as an example dataset under the ‘Energy and Environment’ heading of 14 data areas which are ‘recognised as high value’ (see 6.2 in the technical annex), there was a conspicuous absence of discussion about carbon emissions transparency or data that will be essential to implementing and monitoring commitments to cut emissions.

This reflects a more general lack of prioritisation of climate change at the G8 meeting, which was challenged by France and Germany earlier this year, and picked up on by climate NGOs, protestors and policy experts alike earlier this week.

Apart from a page in the closing 33 page communique, noting that “climate change is one of the foremost challenges for our future economic growth and well-being”, the topic was not treated with the level of gravity or urgency that you’d expect, given the scale of the commitments and energy needed for the world to avoid catastrophic changes in our climate.

There was explicit agreement that the world needs to ‘limit the increase in global temperature to 2ºC above pre-industrial levels’, but – apart from allusions to the next major UN summit on climate change in 2015 in Paris – there was little discussion of how G8 countries will achieve and monitor the emissions cuts that are needed.

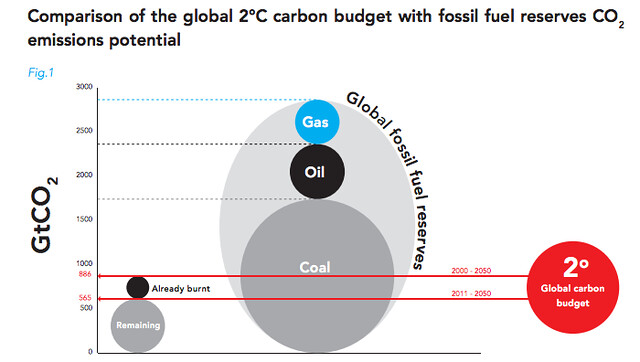

Recent scientific research seems to indicate that to reduce the probability of a 2ºC global temperature increase to below 20%, the world has a total quota of around 886 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide to emit between 2000 and 2050. Estimates suggest that we had already burned our way through around a third of this total quota by 2011 – and the fossil fuel reserves owned by the top 100 listed coal and top 100 listed oil and gas companies alone amount to more than our remaining quota. Known global reserves amount to the equivalent of over 2,795 gigatonnes.

If we want to remain within this 886 gigatonne quota to avoid a temperature rise of more than 2ºC, governments around the world need to start making serious and concrete commitments very soon, and to publish more timely and granular information about how they are performing – so they can be held accountable to their targets.

The UK’s draft order on greenhouse gas emissions reporting requirements for top UK companies is a step in this direction – but it is not explicitly connected with the UK’s open data efforts (the order mentions nothing about the information being made available in machine readable or openly licensed form). Our Advisory Board Member Hans Rosling has managed to secure a commitment from the Swedish government to reduce delays in publication of essential emissions statistics by 6 months – demonstrating that it is indeed possible for countries to publish critical emissions data with less than an 18-24 month delay (a delay which makes it hard for emissions related stories to break into a news culture which places a premium on recency).

We think carbon emissions data should be at the heart of global open data agenda – and we urge open data policy makers, public servants, advocates and civic hackers to join us to make this happen.

If you’d like to find out more about our efforts to open up the world’s carbon emissions data, you can follow #OpenCO2 on Twitter or sign up to our open-sustainability mailing list:

Image credits: Match smoke by AMagill on Flickr (CC-BY). Diagram showing comparison of the global 2°C carbon budget with fossil fuel reserves CO2 emissions potential from the Carbon Tracker Initiative‘s Unburnable Carbon report

Dr. Jonathan Gray is Lecturer in Critical Infrastructure Studies at the Department of Digital Humanities, King’s College London, where he is currently writing a book on data worlds. He is also Cofounder of the Public Data Lab; and Research Associate at the Digital Methods Initiative (University of Amsterdam) and the médialab (Sciences Po, Paris). More about his work can be found at jonathangray.org and he tweets at @jwyg.

Climate change is just not an environmental challenge but a real threat to economic development and poverty reduction. Emissions of CO2 could be addressed in many ways two of which are mentioned here. One is to make efforts to REDUCE the emissions and the other is to find ways and means of ABSORBING the emissions. Members of the G8 must cooperate in REDUCING the emissions generated by their life-style. For ABSORBING they can help to plant trees, develop organic agriculture and expand free-range animal husbandry all of which go to help economic development and poverty reduction at the same time.

A couple of other ways in which openness could benefit poverty reduction in this area, as the previous commenter argued.

First, as the Energy and Climate Change Committee is arguing today, the profits of energy companies should be far more transparent. See http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-23462072

Second, it may not have come to the attention of the average Open Knowledge Foundation supporter that the open access provided to a seminal climate science paper written in 1938 may now save the global community millions if not billions on expensive super-computers and the complex general circulation models coded to run on them. It’s even possible it may save trillions in unnecessary global warming mitigation policies once the implications of the findings are clearer. See http://climateaudit.org/2013/07/26/guy-callendar-vs-the-gcms