On Saturday 7th March 2020, the tenth Open Data Day took place with people around the world organising over 300 events to celebrate, promote and spread the use of open data. Thanks to generous support from key funders, the Open Knowledge Foundation was able to support the running of more than 60 of these events via our mini-grants scheme.

This blogpost is a report by Amy Evans, Stuart Lowe, Patrick Lake and Giles Dring from the Open Data Institute Leeds team in the UK who received funding from Mapbox to host a data surgery to assist attendees with their data, converting the data into GeoJSON files and mapping it.

Open Data Day takes place on the first Saturday of March every year and is a celebration of all things open data. Hundreds of events take place all over the world and it is a wonderful demonstration of the reach and impact of open data, exploring all kinds of topics and sharing knowledge. At ODI Leeds, we were thrilled to be chosen for a mini-grant, which helped us set up our ‘There’s a Map For That’ drop-in session at our innovation space in Leeds.

Mapping and open data work so well together and it’s easier to get started than you might think. There are all kinds of things you can do with a map, and all kinds of data that can be put on a map. Our Data Mapper is a great example of this diversity – there are flood risk areas, recycling centres, electric vehicle charging points, and much more. And all of them powered by open data!

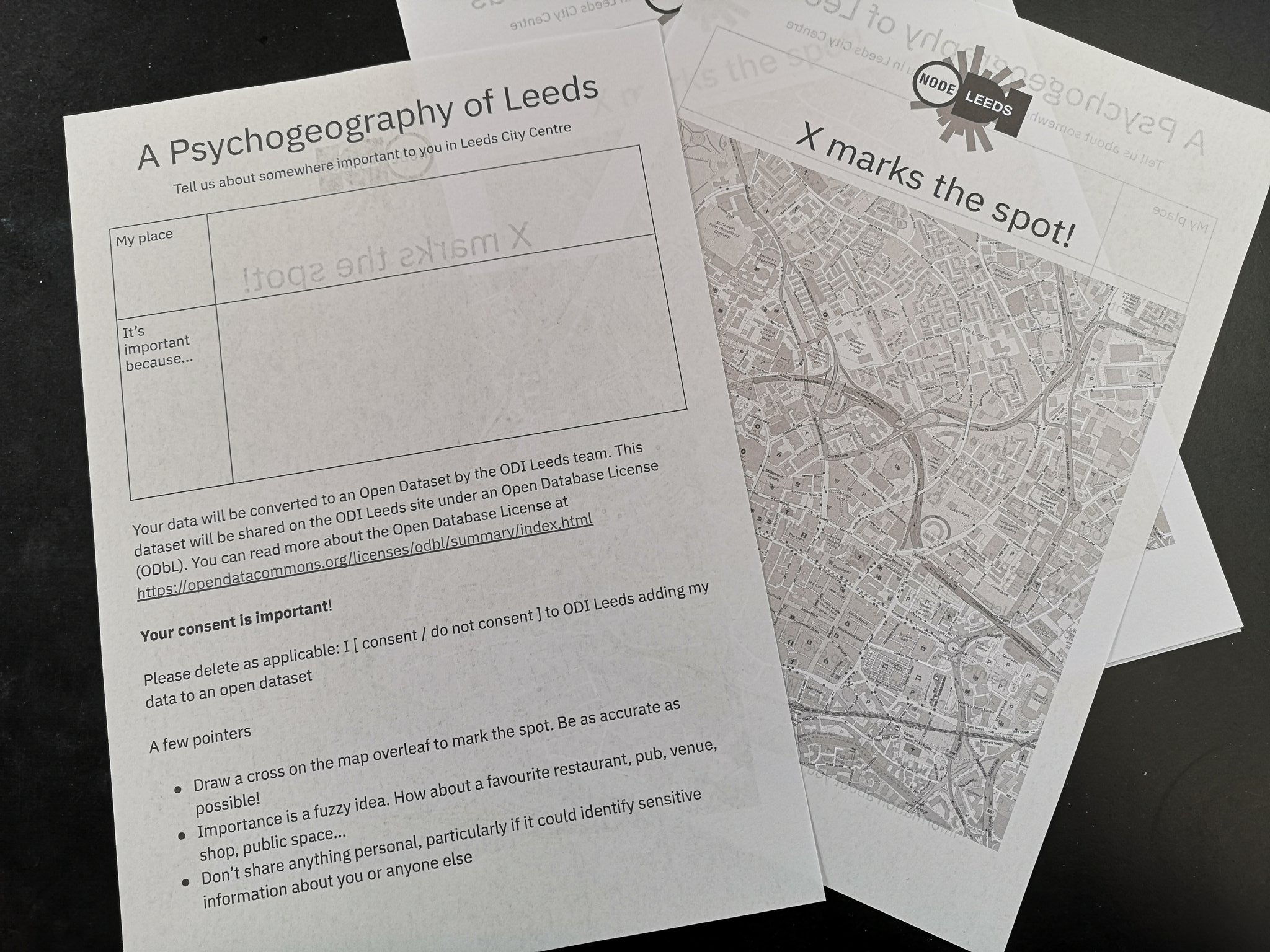

So we put together an informal ‘surgery’ style session for Open Data Day, where people could simply drop-in with their questions or challenges and we would do our best to help. We also prepared some interesting resources and a mapping task of our own as a gentle introduction depending on how many people turned up and when.

It was a small (but mighty) gathering and everyone that attended had some very specific and substantial challenges, some of which are described below.

Our earliest participant arrived with the most hands-on challenge of everyone! Beate, who is a regular of ODI Leeds events, has a particular interest in air quality, specifically how the geography of a place could influence the air quality. In the absence of any answers in official data, she used a Plume personal air quality sensor attached to her backpack and collected her own data! Now she wanted to see if she could get this data on to a map. Giles Dring, our Head of Delivery, helped Beate through it step-by-step.

The first step was to download the data from her Plume account. Plume kindly offers a service to do just this, providing a series of CSV files with the relevant data. Some time was spent understanding the data by loading it into a spreadsheet. The first discovery was that only some of the data was geolocated, but other than that the data was in good shape to be visualised directly.

It was converted into a GeoJSON file using the ODI Leeds CSV to GeoJSON converter tool. Finally, a really simple webpage was created using the Leaflet mapping library. This was a great first step, but the intensity of samples close to Beate’s home could inadvertently leak too much personal information. So the data was aggregated onto a grid which created a simple average of all the readings.

This was done in Excel using a simple rounding of the latitude and longitude figures to create a rough grid, then a pivot table to produce the aggregated table. This was then turned into a Plume flow processing Jupyter notebook after the fact. (Warning: this may require some tweaking to make work!) Running this through the CSV to GeoJSON converter again gave a (much smaller) aggregated file to present, which did just what we needed. Beate then published the website code on GitHub, and turned on GitHub Pages to create an interactive map of the air quality data. Not bad for a mid-morning session!

There’s a lot of scope for more additions to the visualisation – selecting different types of air quality data, the average figure, filtering by time of day – but in all, it was a great introduction to the decisions in publishing data in a map.

Our apprentice Patrick spent some time with Nick, who has been working on a project about land ownership. They wanted to understand situations where a single person or organisation might own lots of land, specifically in the countryside. Nick wanted to know if any of this data was available openly and if so, where could he find it. This is where things get a bit complicated and political. Some data is published openly – commercial and corporate ownership for example, or price paid data – but this data is limited. You can search for property or land information via HM Land Registry, but it incurs a fee per lookup, which is no good for large areas. So where did that leave Nick? Sadly a bit stuck but perhaps not for long. Only a few days later, funding was allocated to HM Land Registry to help bring it back into central government, which could mean more data will be published openly in the future. We offered to keep in touch with Nick and send him any updates that we’re aware of that could help with his project.

Jamie from Bradford Metropolitan District Council (one of our sponsors) popped in to see us about an idea he had in response to the climate emergency. Whilst not directly related to mapping, his challenges definitely had scope to enable future mapping projects within communities, and of course his idea is all about open data and enabling open collaboration. Jamie described his idea as encompassing two parts – a dashboard that displayed the number of climate projects taking place in Bradford; and the open ‘repository’ where the projects could all be collected together, allowing for people to add their project in a standardised way. Stuart, who works on our data projects, suggested that Github was a good place to start. We use it at ODI Leeds for a variety of things and it has a slew of other benefits as well. By the end of the session, a brand new Github account had been created for Bradford Metropolitan District Council, all primed and ready for the first project. This idea had been brewing in Jamie’s mind for a while, and our drop-in session on Open Data Day was the perfect opportunity to talk to us, to sound out his ideas in a neutral environment before committing to anything. Our sponsors are important to us – through their support, we are able to host events like #PlanetData or work on projects like the hexmaps – and we continually keep their priorities and ambitions in mind as we work with them or start new projects. So getting to spend some time thinking about this climate project dashboard with Bradford was brilliant.

Our Open Data Day event might have been small, but it had a huge impact for those that attended. It also gave us something to think about in terms of creating learning resources for open data mapping. Should we put together a simple learner’s pack to take some physical mapping exercises into the open data world? We have some technical posts about useful tools that can help with preparing data for mapping but what about a start-to-finish tutorial? We love to create useful things for others, because ultimately, open data is for everyone. If more people can feel confident to tell their stories with data, we all benefit from richer perspectives and previously unrecognised potential in data.