Some weeks ago, the European Commission proposed an update of the PSI Directive**. The PSI Directive regulates the reuse of public sector information (including administrative government data), and has important consequences for the development of Europe’s open data policies. Like every legislative proposal, the PSI Directive proposal is open for public feedback until July 13. In this blog post Open Knowledge International presents what we think are necessary improvements to make the PSI Directive fit for Europe’s Digital Single Market.

In a guest blogpost Ton Zijlstra outlined the changes to the PSI Directive. Another blog post by Ton Zijlstra and Katleen Janssen helps to understand the historical background and puts the changes into context. Whilst improvements are made, we think the current proposal is a missed opportunity, does not support the creation of a Digital Single Market and can pose risks for open data. In what follows, we recommend changes to the European Parliament and the European Council. We also discuss actions civil society may take to engage with the directive in the future, and explain the reasoning behind our recommendations.

Recommendations to improve the PSI Directive

Based on our assessment, we urge the European Parliament and the Council to amend the proposed PSI Directive to ensure the following:

- When defining high-value datasets, the PSI Directive should not rule out data generated under market conditions. A stronger requirement must be added to Article 13 to make assessments of economic costs transparent, and weigh them against broader societal benefits.

- The public must have access to the methods, meeting notes, and consultations to define high value data. Article 13 must ensure that the public will be able to participate in this definition process to gather multiple viewpoints and limit the risks of biased value assessments.

- Beyond tracking proposals for high-value datasets in the EU’s Interinstitutional Register of Delegated Acts, the public should be able to suggest new delegated acts for high-value datasets.

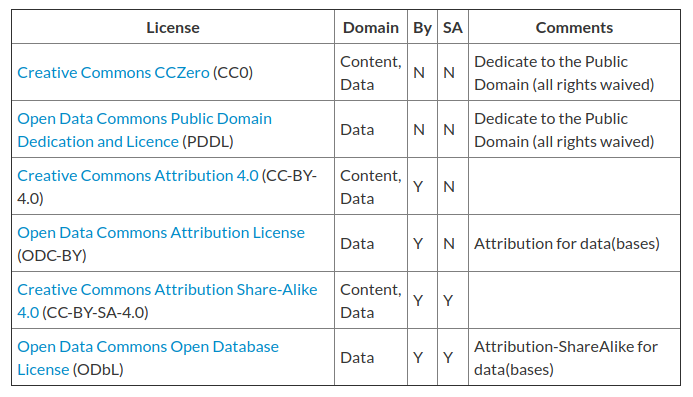

- The PSI Directive must make clear what “standard open licences” are, by referencing the Open Definition, and explicitly recommending the adoption of Open Definition compliant licences (from Creative Commons and Open Data Commons) when developing new open data policies. The directive should give preference to public domain dedication and attribution licences in accordance with the LAPSI 2.0 licensing guidelines.

- Government of EU member states that already have policies on specific licences in use should be required to add legal compatibility tests with other open licences to these policies. We suggest to follow the recommendations outlined in the LAPSI 2.0 resources to run such compatibility tests.

- High-value datasets must be reusable with the least restrictions possible, subject at most to requirements that preserve provenance and openness. Currently the European Commission risks to create use silos if governments will be allowed to add “any restrictions on re-use” to the use terms of high-value datasets.

- Publicly funded undertakings should only be able to charge marginal costs.

- Public undertakings, publicly funded research facilities and non-executive government branches should be required to publish data referenced in the PSI Directive.

Our recommendations do not pose unworkable requirements or disproportionately high administrative burden, but are essential to realise the goals of the PSI directive with regards to:

- Increasing the amount of public sector data available to the public for re-use,

- Harmonising the conditions for non-discrimination, and re-use in the European market,

- Ensuring fair competition and easy access to markets based on public sector information,

- Enhancing cross-border innovation, and an internal market where Union-wide services can be created to support the European data economy.

Our recommendations, explained: What would the proposed PSI Directive mean for the future of open data?

Publication of high-value data

The European Commission proposes to define a list of ‘high value datasets’ that shall be published under the terms of the PSI Directive. This includes to publish datasets in machine-readable formats, under standard open licences, in many cases free of charge, except when high-value datasets are collected by public undertakings in environments where free access to data would distort competition. “High value datasets” are defined as documents that bring socio-economic benefits, “notably because of their suitability for the creation of value-added services and applications, and the number of potential beneficiaries of the value-added services and applications based on these datasets”. The EC also makes reference to existing high value datasets, such as the list of key data defined by the G8 Open Data Charter.

Identifying high-quality data poses at least three problems:

- High-value datasets may be unusable in a digital Single Market: The EC may “define other applicable modalities”, such as “any conditions for re-use”. There is a risk that a list of EU-wide high value datasets also includes use restrictions violating the Open Definition. Given that a list of high value datasets will be transposed by all member states, adding “any conditions” may significantly hinder the reusability and ability to combine datasets.

- Defining value of data is not straightforward. Recent papers, from Oxford University, to Open Data Watch and the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data demonstrate disagreement what data’s “value” is. What counts as high value data should not only be based on quantitative indicators such as growth indicators, numbers of apps or numbers of beneficiaries, but use qualitative assessments and expert judgement from multiple disciplines.

- Public deliberation and participation is key to define high value data and to avoid biased value assessments. Impact assessments and cost-benefit calculations come with their own methodical biases, and can unfairly favour data with economic value at the expense of fuzzier social benefits. Currently, the PSI Directive does not consider data created under market conditions to be considered high value data if this would distort market conditions. We recommend that the PSI Directive adds a stronger requirement to weigh economic costs against societal benefits, drawing from multiple assessment methods (see point 2). The criteria, methods, and processes to determine high value must be transparent and accessible to the broader public to enable the public to negotiate benefits and to reflect the viewpoints of many stakeholders.

Expansion of scope

The new PSI Directive takes into account data from “public undertakings”. This includes services in the general interest entrusted with entities outside of the public sector, over which government maintains a high degree of control. The PSI Directive also includes data from non-executive government branches (i.e. from legislative and judiciary branches of governments), as well as data from publicly funded research. Opportunities and challenges include:

- None of the data holders which are planned to be included in the PSI Directive are obliged to publish data. It is at their discretion to publish data. Only in case they want to publish data, they should follow the guidelines of the proposed PSI directive.

- The PSI Directive wants to keep administrative costs low. All above mentioned data sectors are exempt from data access requests.

- In summary, the proposed PSI Directive leaves too much space for individual choice to publish data and has no “teeth”. To accelerate the publication of general interest data, the PSI Directive should oblige data holders to publish data. Waiting several years to make the publication of this data mandatory, as happened with the first version of the PSI Directive risks to significantly hamper the availability of key data, important for the acceleration of growth in Europe’s data economy.

- For research data in particular, only data that is already published should fall under the new directive. Even though the PSI Directive will require member states to develop open access policies, the implementation thereof should be built upon the EU’s recommendations for open access.

Legal incompatibilities may jeopardise the Digital Single Market

Most notably, the proposed PSI Directive does not address problems around licensing which are a major impediment for Europe’s Digital Single Market. Europe’s data economy can only benefit from open data if licence terms are standardised. This allows data from different member states to be combined without legal issues, and enables to combine datasets, create cross-country applications, and spark innovation. Europe’s licensing ecosystem is a patchwork of many (possibly conflicting) terms, creating use silos and legal uncertainty.

But the current proposal does not only speak vaguely about standard open licences, and makes national policies responsible to add “less restrictive terms than those outlined in the PSI Directive”. It also contradicts its aim to smoothen the digital Single Market encouraging the creation of bespoke licences, suggesting that governments may add new licence terms with regards to real-time data publication. Currently the PSI Directive would allow the European Commission to add “any conditions for re-use” to high-value datasets, thereby encouraging to create legal incompatibilities (see Article 13 (4.a)). We strongly recommend that the PSI Directive draws on the EU co-funded LAPSI 2.0 recommendations to understand licence incompatibilities and ensure a compatible open licence ecosystem.

I’d like to thank Pierre Chrzanowksi, Mika Honkanen, Susanna Ånäs, and Sander van der Waal for their thoughtful comments while writing this blogpost.

Image adapted from Max Pixel

** Its’ official name is the Directive 2003/98/EC on the reuse of public sector information.

Danny Lämmerhirt works on the politics of data, sociology of quantification, metrics and policy, data ethnography, collaborative data, data governance, as well as data activism. You can follow his work on Twitter at @danlammerhirt. He was research coordinator at Open Knowledge Foundation.